The Art and Politics of Nicolas Columbo By Diana Griffith

I interviewed Nicolas Columbo one rainy evening over Old-Fashioneds made with good Jameson whiskey. Like an itch I just had to scratch, I moved in slowly, wanting to exchange pleasantries about the patron system, how internet sales of art has minimized the gallery experience, and the differences that exist between naive artists versus established artists. These are all valid topics, and Nicolas has interesting things to say about all these things. But as the itch became more intense, and quite possible because of the Jameson, I finally dove in. At the risk of alienating him and becoming too personal, I asked about how his politics informs his art. And that was when things got really, really good. He points with the hand that holds the drink, “More than being an artist, I am a social critic, and that is where all my inspiration comes from.” As a 1994 graduate of Pacific Northwest College of Art, Columbo has been involved in film making, film editing, music, and fine art. Columbo insists he has been interviewed more as a musician than an artist. He finds the fluid nature of how an artist can move easily between these genres very appealing, and is quick to point out that Portland is an easy city to find supportive collaborators to aid in this movement from one to the other. As he has aged, it seems it has become easier for him to have collaborative alliances, but in the beginning it was not so. “I've destroyed more work than I've shown”, he says to me while taking a smoke break. “Yeah, there's always an element of self-loathing in an artist”, he nods acceptingly. Nicolas claims the early 20th century artist, Alberto Giacometti, is someone he relates to. Both volatile and easily misunderstood, Giacometti and Columbo share more than Italian ancestry. After a quick overview of the B.F.A. program at Pacific Northwest College of Art, I realize that Columbo is holding out on me. So I ask, “Nick, how did you learn so much about political science and world history?” “I study life on my own”, he quips, “and most of my free time I spend reading. And I don't think of myself as particularly classically educated.” “I beg to differ”, I shoot back with a grin. Humbly, looking down at the ground me admits, “Well, at university all I studied was art. But I also felt as a kid I had a good grasp of human nature. And when I was a child I think my mother nurtured that. But when I got a little older, I think she worried about it. I think my mother felt like the arts led to drug abuse, and depression, and sadness.” Columbo asserts that significant art can arise from these places of pain. He is estranged from many members of his family whom he said he never got the chance to know that well. Political and cultural heroes, manufacturing what they feel compelled to, have influenced him greatly. And that was my introduction to the real impetus behind Columbo's desire to create. If not for radically progressive political ideas, Columbo's art would be rather tedious. Turns out, Columbo is a self-described “political advocate for the inequality in American.” OK, Nick, you had me at “self-loathing.” When looking at his work, Columbo wants that viewer to turn to the person next to him and start a conversation about it. And if no one is standing next to the viewer, he wants said viewer to “run down the street and drag someone out of their car to talk about the piece...that's a good thing! This kind of art wants to start a conversation. This kind of art wants to get your mind moving!” And so the conversation progressed. Columbo asserts that Michelangelo and Leonardo were “graphic artists for god”, and that their work has withstood the test of time as being monumentally important. But was it political? Was it even meant to be? Not so much. It was only political in the sense that it was meant as a visual reference to assert control over a people. Columbo likes to tell the story of the surrealist painter Max Ernst, who was imprisoned by the Gestapo in Nazi occupied France during World War II. Ernst was asked by the prison to paint something. The warden did not give specifics about subject matter, and Ernst was left to his own creative imagination. Which turned out to be a mistake--it was reported that Ernst painted a female nude, in typical surrealist style, the way only Ernst could do. With a beaming smile, Columbo exclaims, “And the warden just loses his shit over how perverted Ernst's work is. And the painting is destroyed!” This makes Ernst a hero in Columbo's eyes. Ernst could have painted a Nazi propaganda piece in order to massage the egos of the warden and as a consequence quite possibly help Ernst's time in prison be more comfortable. Ernst could have illustrated the archetypical Arian goddess, or benevolent Nazi guard in oil on canvas. This mistake kept Ernst in prison for another year. But it was worth it. Willem de Kooning is also a hero of Columbo's. There were rumors for years that the abstract expressionism practiced by de Kooning was secretly (unbeknownst to even de Kooning) used as a Central Intelligence Agency tool during the Cold War. Apparently, there were many artists considered undesirable to the U.S.S.R. after the war, and although de Kooning was from the Netherlands, the U.S.S.R. was still disapproving of such artists. De Kooning became an expatriate. The United States wanted to be viewed as a nation open to intellectual thought, and secretly promoted de Kooning's work as well as other abstract expressionists as a way to “stick it to Russia” and show how well the nation could nurture such avant-garde thought, and used this as a way to juxtapose it to the rigid and suffocating environment of the U.S.S.R. Enter Joseph McCarthy, who apparently was not “in on it”. He wasn't notified of this secret promotion of intellectual art and therefore rallied against art that didn't, at least figuratively anyway, portray pictures of kittens and puppies. Here was de Kooning, caught in the middle of a battle he did not create, and as Columbo puts it, “de Kooning was used to destroy and fragment youth through infiltration and deception. And as a consequence, there is this huge backlash against revolutionary thought.” Columbo espouses, “Revolutionaries die and become unpopular. And we see this same theme over the spectrum of the arts and popular culture.” “But Nicolas”, I chime in as the next smoke break begins, “what revolutionary thought do you want to express in your work?” And that brings me the art series that I think Nicolas Columbo is best known for. Thematically, these paintings are black and white oil on canvas works that he calls “Images of the Hood”. And the series hybridizes the two things he was most fascinated with after 2003. These two topics are intrinsically linked because of Columbo's obsession with:

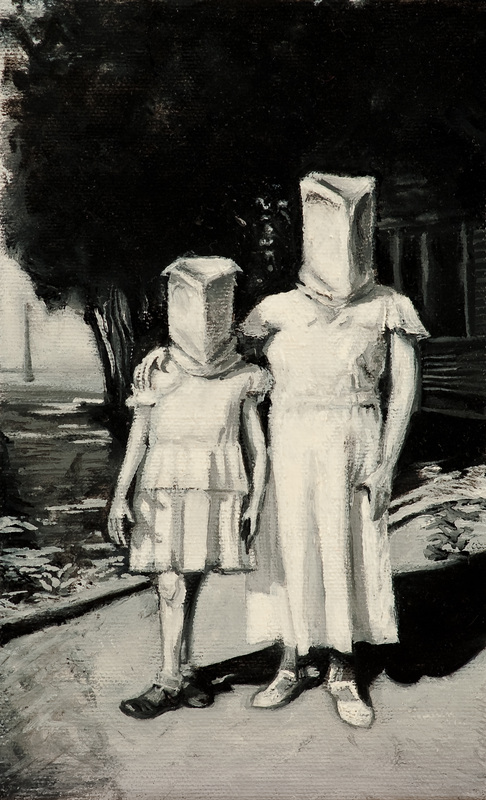

Columbo's portraits are done in high mid-century modern fashion. The photos used as inspiration in the portraits are from the days when women wore white gloves and pearls to dinner. Women and men were rarely seen without hats when outside. And the suits were slick and minimalist. Ties thin and pant cuffs with just a perfect break at the ankle. Even the outdoor photos show the emergence of the mid-century modern ranch, complete with swimming pool in the backyard. The paintings are delicious, and Columbo has painted them with thin glazes of oil such that the subjects look luminous and transparent. And then there are the hoods on the heads of Columbo's subjects. Columbo says emphatically, “When I started doing these portraits of my family with bags on their heads, I took maybe seven, eight, or nine boxes of photographs of my father's. I saw all these people I did not know and I had to make this leap between the physical, horrible real world, of rendition and political persecution of post 9/11, and this analytical viewpoint that asks us to examine how we feel about being able to steal someone away from their identity.” And that's a pretty big leap, I'm thinking to myself. “Did viewers get that”, I ask. “It surprises and shocks the shit out of me that I could create a painting of someone with a hood on his head in 2008 and no one makes that leap”, he says with a deadpan stare. Columbo really lets me know how far I have to go as a viewer of art, and appreciator of art, “The hood that I painted on my subjects is the ultimate dehumanization of the human”. “Why aren't you teaching anymore Nick?” I ask as I fill our glasses for the last time. “A lot of my professors have told me I should teach again. And I love academics, but I honestly abhor the university system in the States because I believe higher education should be free. I believe that is the only honest, true system. And I believe that both with healthcare and education. Neither of these things should be commodities and neither should they be made for profit. If we want to pretend we are living in an enlightened societal age, we should be willing to make these commitments to each other.” In so many ways Nicolas Columbo says what is simple and what needs to be said. And in so many ways he says with his art and his political views, things that are quite complex. I have decided that Nicolas Columbo is simply complex. I know, I know. It doesn't have to make sense. Nicolas Columbo lives and creates in Portland, Oregon. See more of his work at: http://www.flickr.com/photos/ncolumbo/ http://www.nicolascolumbo.tumblr.com/ |